'Three Sober Preachers', oil paint on canvas, c.1860

The Tate, of course, is an art museum, and this exhibit is an exuberant celebration of the art we come across in our everyday lives – shop signs, for example – and the art we make in the everyday task of living, such as making quilts from scraps, collages from found objects, and driftwood sculpture.

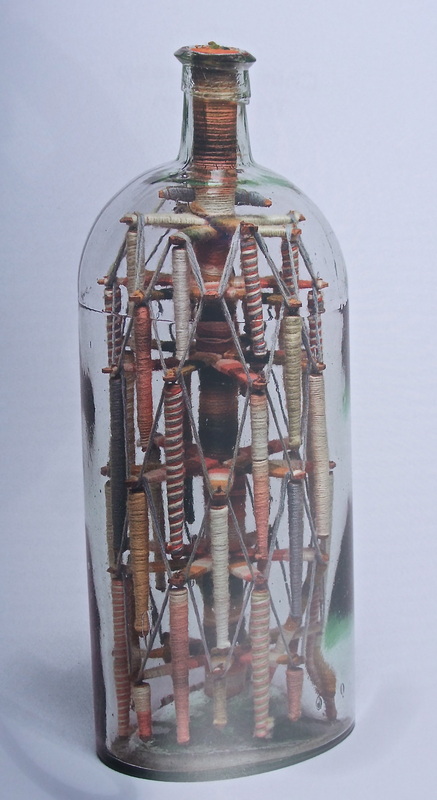

| Not all of these have function as their primary purpose – one of the possible definitions of ‘craft’ as distinct from ‘art’. But nor do they necessarily have something to 'say' in the sense of deeper meaning. Many display great innovation and originality - such as the boody pieces from the north of England, using broken china (called 'boody') to create mosaic tins and boxes in the late 19th century - but weren’t created to convey an idea or emotion. With others, the purpose is unknown, such as the God–in-a-Bottle pieces associated with the construction workers and miners who were part of the Irish Catholic diaspora. |

| Raw it may be, but at least one folk artist made much of his royal connections. George Smith was a tailor in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, in the early 19th century. He described himself as “Artist in Cloth and Velvet Figures to His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex”. His fabric and paper collages, such as this one in a series from 1830-40 called 'The Goosewoman', became a tourist attraction. |

| The work of Alfred Wallis shows how ‘folk’ makers were sometimes feted by established artists. Wallis was ‘discovered’ by Modernist artist Ben Nicholson in an unexpected encounter in Cornwall, where Wallis had been using old pieces of cardboard as the canvases for his paintings. Perhaps what matters is our response to the work - the meaning or intention we infer as viewers, the emotions that the piece triggers in us personally. |

Many of the pieces in the exhibit are rooted in the notion of community identity – whether the community of a courting couple who together produced the Bellamy quilt during their year-long engagement, or the members of the community who contributed to the production of shop signs.

Wherever you stand on the art/craft debate (or indeed whether or not you see any distinction), you're sure to enjoy the works in this show and the questions they provoke.

British Folk Art is on at Tate Britain until 31 August 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed