Signs and Wonders

We recently re-launched the free 10-minute introductory talks offered at the Grand Entrance to the museum. During the madness of Savage Beauty, the wildly popular exhibit on the work of designer Alexander McQueen, we had to take down our sign offering these to make room for the crowds queuing for tickets to the sell-out show. Now that it’s calmer, we’ve started again, this time with a hand-held sign. Not everyone wants an introduction, but many new visitors seem to welcome a quick guide to the vast collections.

If I have the luxury on focusing their attention on one piece, I choose Signs and Wonders by Edmund de Waal. This is what I say:

Welcome to the V&A, the world’s greatest museum of art and design. A schoolroom for everyone – that’s the way its first director, Henry Cole, described it - a welcoming place to inspire and provoke. We are free, we are open every day, and we open late on Fridays.

De Waal describes the pieces in this work as “a kind of love story with the ceramics collections, and they’re a kind of conversation with the collections at the V&A, they’re a kind of a very personal memory of my journeys through the V&A’s ceramics collections over the last 30 years”. He chose this location because it’s the one place in the whole of the V&A that connects the ground floor, the threshold, with those great galleries.

| The V&A’s ceramics collection is unrivalled in the world and includes more than 34,000 objects from the 4th millennium BC to the present day. The collection is particularly rich in Ceramics from Asia, the Middle East and Europe. The Victorian founders of the V&A aimed to influence taste by collecting and displaying examples of the best designs, from ironwork to textiles, jewellery to pottery. Alongside British ceramics were gathered pieces from Europe, India, China, Japan, Turkey, Morocco and Iran. They range from a Coptic jar from 5th century Egypt to a vase by contemporary artist Grayson Perry. |

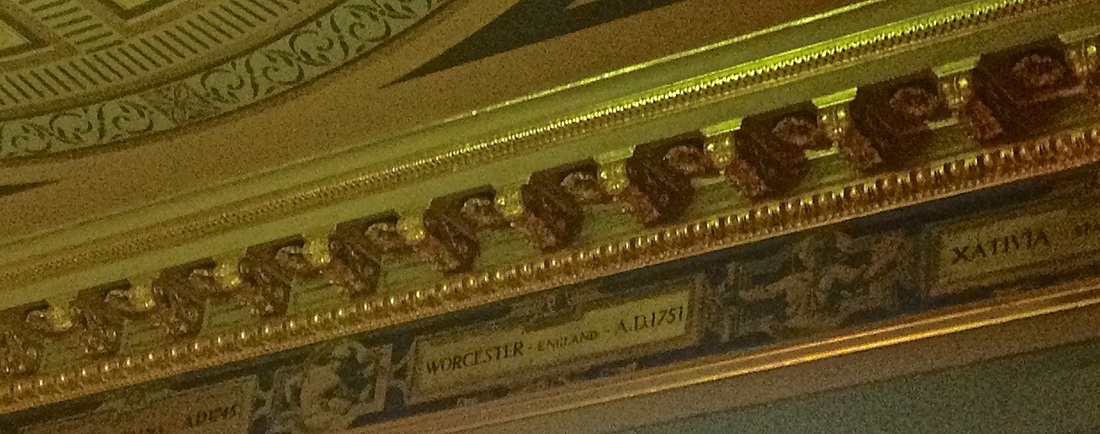

The new ceramics galleries opened in 2010. They attempt to tell significant stories of ceramic history, and unlike the previous arrangement of collections, they now juxtapose pieces from Asia and Europe, showing the influence of different cultures on one another. Gone are the dark cabinets, and instead we can see through the glass of one cabinet into another.

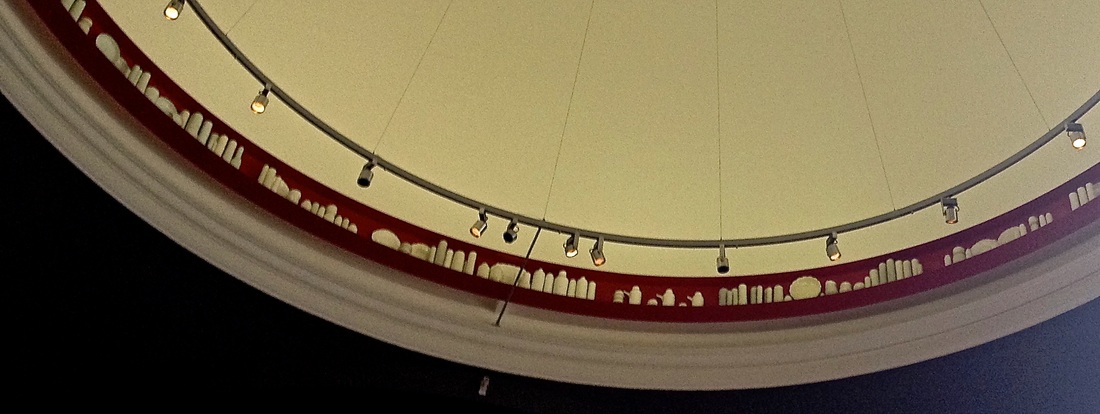

This fits in well with De Waal’s vision for his installation. He often works with what he calls ‘cargoes’ of pots, groups or multiples that make connections between cultures. Influenced by Japanese porcelain pottery, de Waal says he’s drawn to its naturalness and to its “contradictory notions of strength and fragility”. Each of the 425 pots is a shade of white, contrasting with the red lacquer steel shelf. The red colour is intentional, evoking the red seal in the corner of ink paintings.

pot after pot after pot, pots layered on pots, ‘a collection of collections’

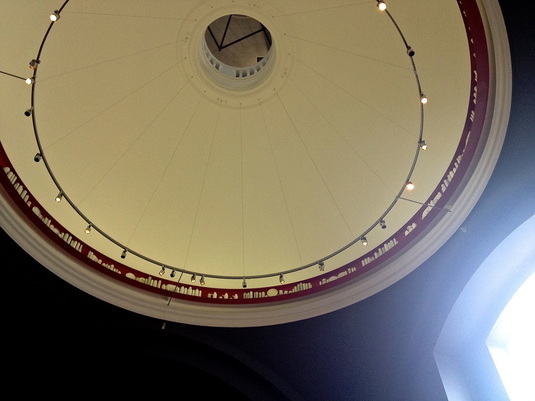

De Waal describes his piece as “responding to the specific architecture of the place”. The shelf tracks the circumference of the dome, held in only four places – an astonishing and complex engineering feat that provides a link between past (the 1909 galleries as they were) and present (the new galleries), and between the ground (the Grand Entrance) and the unreachable heights of the dome.

One attraction for me is the way the ceramics galleries (although this holds true of many of the other galleries as well) blurs the line between art and craft – an often arbitrary and unnecessary distinction.

De Waal is one of many of Britain’s, and the world’s, most successful designers, artists and craftspeople who have used the V&A as a source of ideas and stimulation over the past 150 years: Arts and Crafts pioneers William Morris and William de Morgan (Islamic design), children’s author Beatrix Potter (textiles), Italian designer Alessi (Dresser), among others. Everyone is welcome to come here to see the work of these artists alongside the historic collections that helped to inspire them.

I hope you enjoyed this introductory talk!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed