The year of 2017 will be bookended by women speaking out about sexual harassment. And these bookends are both captured visually in two designs created by women: the pink pussyhat and the #metoo hashtag. Both were created as visual symbols of, and means of communicating, women's anger and outrage. They've been hugely influential, spearheading vital and timely campaigns. Yet their adoption has contributed to a wildfire spread in which the original aims and intentions risk being lost. Can these design icons serve as a focal point to help people discuss sexual harassment and improve the level of debate? Or do they serve as visual symbols of the co-option of anger for media and marketing purposes? We need to talk about this, and we need to talk about talking better.

Time magazine, February 2017

Time magazine, February 2017 At the Women’s March in January, held throughout the world to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump as US President and misogynist-in-chief, more than 4 million people in 600 cities donned knitted pink hats to show solidarity. The hats are part of the Pussyhat Project, an initiative founded by screenwriter Krista Suh and architect and activist Jayna Zweiman after the 2016 Presidential election. Suh and Zweiman worked with a knitting-shop owner, Kat Coyle, to design the pussyhat, its cat ears inspired by a recording released during the election campaign in which Trump is heard joking with Billy Bush about grabbing women ‘by the pussy’, a form of sexual assault which he discounted as ‘locker room banter’ in his defence.

The intention of the Pussyhat Project was to create a striking, collective visual expression of women’s anger. One of the project’s primary aims is to develop meaningful, respectful connections among people who care about women’s rights. The movement also aimed to provide a way for people who couldn’t physically attend a march to join the protest by knitting a hat for a marcher.

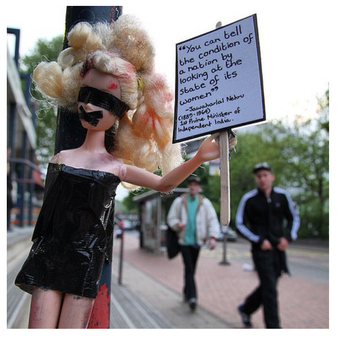

This origin story echoes the many ways craft and revolution have intersected for hundreds of years - think Sarah Corbett and her Craftivist Collective, spearheading campaigns to highlight issues of social justice through ‘mindful activism’, ‘reflection and respectful conversation’. Below is one of her projects, quoting Nehru and placed outside Clapham Junction Station in London as a comment on the way women’s voices are often unheard. Corbett explains, ‘Often the boys would have their arms around their girlfriends and the girls would not talk much. It made me uncomfortable and I wanted to challenge it.’

| The pussyhat has achieved icon status as an example of protest design. It has been named as one of the top ten museum acquisitions in 2017, and one is on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Rapid Response Collecting gallery, which explores how current global events, political changes and pop cultural phenomena impact, or are influenced by, design, art, architecture and technology. Corinna Gardner, the V&A's Acting Keeper of the Rapid Response Gallery, explains the importance of the pussyhat: ‘This modest pink hat is a material thing which, through its design, enables us to raise questions about our current political and social circumstance. Worn by thousands across the globe on 21 January 2017, the Pussyhat has become an immediately recognisable expression of female solidarity and symbol of the power of collective action.’ |

Mihai Surdu, Pixabay.com

Mihai Surdu, Pixabay.com October 2017

One of the dangers, however, is that a design icon for a social movement can quickly become adopted as a marketing brand and lose meaning and power – or at least its power can be co-opted by forces that distort the original aims. The pussyhat was named Brand of the Year by SVA in one of many competitions established 'in an effort to understand, measure, mark, and codify the meteoric'. It was honoured not for its contribution to capitalism but in recognition of its democratising purpose: 'created by the people, for the people—and it brings people together for the benefit of humanity'. Yet this award calls into question whether the design icon has lost its origin story in its adoption as a marketing brand. What does it now mean?

This question is as true for the pussyhat as it is for the #metoo Twitter hashtag, which recently has been at the forefront of a sexual abuse scandal primarily focused on the upper echelons of US and UK public life. The scandal has been a gift to the media. There is no better illustration of this co-option than the full-page spread published by the New York Times this month, with a 'shame' list of 40 prominent men who had resigned or been sacked as a result of sexual abuse allegations.

Pussyhat co-founder Zweiman has linked the Pussyhat movement with the #metoo Twitter hashtag, which was created in 2006 by social activist and community organiser Tarana Burke as part of a grassroots campaign to promote 'empowerment through empathy' among women of colour who have experienced sexual abuse. Burke reports that she was inspired to use the phrase after being unable to respond to a 13-year-old girl who confided to her that she had been sexually assaulted. Burke later wished she had simply told the girl, 'me too'. In light of the allegations about sexual abuse by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, in October 2017, actor Alyssa Milano revived the use of #metoo as a way to give voice to all women who had experienced sexual harassment and abuse and to illustrate the magnitude of the problem. It was quickly adopted, and has trended in more than 85 countries; arguably it has sparked what has become, in late 2017, a storm of sexual harassment and assault allegations against men in power, primarily in the media and political spheres.

Although Milano acknowledged Burke as the designer of #metoo, the original focus on the experiences of black women has been lost in the ensuing maelstrom. Furthermore, the celebrity stardust that accompanies the current storm runs the risk of ignoring the everyday experiences of sexual harassment and abuse that all women, from all spheres of life, face in a system that is still fundamentally patriarchal and sexist. Burke herself has said that she would like us to move away from a focus on the alleged abusers and the 'celebrity scandal' and focus on survivors and on the systemic issues that allow sexual violence to flourish.

Feminism has not always grappled successfully with intersectionality. In Bad Feminist, Roxanne Gay writes about feminism, with all its flaws, helping her to find her voice. But she also notes that feminism has failed to embrace women of colour, transgender women, and poor women and has failed to address intersectionality, the multitude of factors in our identities (race, gender, sexuality, disability) which are not isolated but are interwoven and shape our experiences, including experiences of harassment and abuse. When a movement or protest focuses on only one aspect (eg gender) it can misrepresent how oppression of discrimination (eg sexism) is experienced by individuals. This is but one example of the ways in which the current debate about sexual harassment and abuse has betrayed the intentions of the #metoo designer.

Friederike Pezold, Pudenda-Work, 1973-74

Friederike Pezold, Pudenda-Work, 1973-74 Michigan State University’s Museum has collected pink pussyhats as part of their protest materials archive and intends to use the hats as part of ‘Difficult Dialogue’ talking circles. The Museum’s Director says, ‘The conversations won’t be easy, we realise, but at a time when our nation is so polarised over so many seemingly intractable issues, we need to learn, all over again, how to listen to one another.’

We need more 'Difficult Dialogues' right now. I fear we're not listening to each other, and I wonder to what extent the design icons that have made the pussyhat and #metoo movements so prominent have contributed to that. Social media invites branding, trending and quick response; it doesn't lend itself to careful consideration of the issues. It doesn't tolerate uncomfortable viewpoints and opinions. And it is no place for those who just feel confused. Writing about the often kneejerk reactions to sexual harassment allegations in higher education, Alison Phipps suggests that punitive, 'zero tolerance' responses unhelpfully conflate behaviours and obscure the roots of individual behaviour. Although I think individual misbehaviour and harassment should be called out, I do agree with Phipps when she says, 'Dysfunctional systems can’t be fixed by purging a few individuals. This is what I call "institutional airbrushing" – the visible blemish is removed and the underlying malaise left to fester.' Culture change is what's needed, and honesty about the systemic forces at play.

Phipps touches on the dangers of ignoring intersectionality, which she says 'pushes us to understand our lives as complex mixtures of victimhood and perpetration'. A crude explanation of what constitutes sexual harassment or abuse, and a one-size-fits-all approach to remedying it (though only superficially, by securing trophy heads on pikes), gets us no further in our understanding or our ability as a society to remedy the problem. And it leaves many women's experiences unrecognised: 'Seeking justice on sexual harassment without acknowledging the injustices built into the fabric of institutions will protect some at the expense of others.'

Where are the men's voices in all this? Not the men who absurdly claim they don't know what's acceptable anymore in terms of touching or commenting, and not the men, like US Vice-President Pence, who insist they will not meet or dine with a woman other than their own wives (the absurd 'Pence Rule'). We don't hear much from the men who have been accused of sexual harassment or abuse. But we hear even less from men who haven't been and who may feel wary of speaking up, of saying the 'wrong' thing. We need to recognise that among the clear red lines of unacceptable behaviour there are a range of acceptable responses that women can make. There is also, dare we say it, a level of ambiguity in interpretation and nuance and context.

We need to be having better and more robust conversations. If 2016 was newly shocking in its assaults to our political sensibilities, 2017 is depressingly retrograde. It has continued to bring in disruption (of the good and bad kind) on a massive level, but the tenor of debate remains depressingly superficial.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed