Thomas Moore, 1813

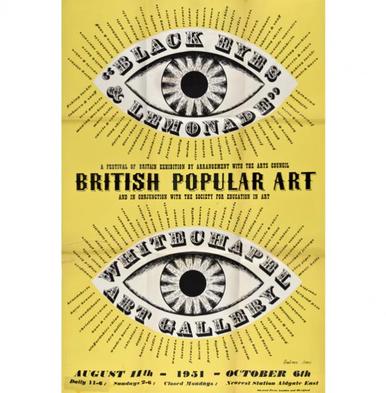

Catch it while you can! The exuberantly fun Black Eyes and Lemonade exhibit at Whitechapel Gallery is on only until next month. It celebrates the work of Barbara Jones (1912-78), the collector and curator of English popular art and author of The Unsophisticated Arts (1951). Specifically, it celebrates an exhibition curated by Jones for the Festival of Britain in 1951.

| What is popular art? Is it as simple as the art of the everyday? Jones herself found it hard to define, but said the best of it is bold and fizzy (hence the name for the exhibit chosen by the curators). It certainly is that. In effect it’s an archive exhibit, re-creating much of the original collection exhibited by Jones at the Whitechapel as part of the Festival of Britain. The gallery blurb describes the original exhibit as: “…divided in categories such as Home, Birth-Marriage-Death, Man’s Own Image and Commerce & Industry, reflecting Jones’s ideas on popular art and museum culture, questioning the cultural values attached to handmade and machine made objects.” |

Art director Simon Costin writes about Jones and the Black Eyes and Lemonade exhibit in a post on blog Caught by the River. Jones, Costin says, collected objects with "long folkloric histories, such as horse brasses, corn dollies, canal boat artwork, ships’ figureheads, and the pearly King & Queen outfits." But in bringing these together with "post-industrial advertising devices like the Idris Talking Lemon, beer mats, pest control adverts, shop posters", Jones

"...gave ‘folk art’ or ‘popular art’ a cultural currency, she made it relevant, exciting. And by putting the machine-made and the hand-made side by side, she blurred the boundaries between what was considered art, liberating a way of seeing that continues to widen our appreciation of the ordinary, the everyday."

I was reminded of Kurt Schwitters, the German artist who devised the concept of Merz in his collages. (Tate Britain recently had a fascinating retrospective of Schwitters’ work.) He incorporated found objects and litter, sweet wrappers and used bus tickets in his work, giving equal value to the everyday and the fine, the costly and the cheap.

| In 1919 Schwitters defined Merz as: “essentially the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes, and technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials….A perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton wool are factors having equal rights with paint.” A refugee from Germany to Norway, then to England when the Germans invaded Norway in 1940, Schwitter was interned as an enemy alien for more than a year. After he was released he moved to London, where he collected discarded litter on the streets to use in his work. He was fascinated with English words and phrases and often used bits of newsprint and magazines in his collages. Unlike Jones, however, his work shows an ambivalence, even cynicism, about contemporary popular culture, especially the post-war plenty in the US and its contrast with the austerity that governed daily life in most of Europe at the time. |

Black Eyes and Lemonade, Whitechapel Gallery, free, until September 2013.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed