[Wo]Mankind

Elizabeth Bishop, Exchanging Hats, Carcanet (1997)

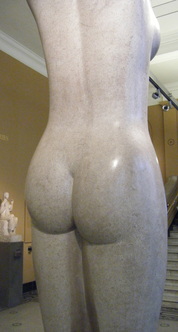

| I often wonder if visitors are shocked to be greeted by a large and luscious bare behind when they come to the V&A. When you enter the museum from the Exhibition Road entrance or the tunnel from South Kensington tube station, you’re immediately met with Eric Gill's larger-than-life sculpture of a nude woman. Carved from a single piece of Hoptonwood stone, it's a modern-day Venus de Milo and is smooth and round and very tempting to touch. Gill, who started out as a stone mason and letter cutter, features in our day-to-day lives more than many visitors might realise, but not for works like Mankind. Many of his works commissioned by public bodies (including for the BBC's Broadcasting House and the headquarters of London Transport) are well-known landmarks around London. He designed a number of typefaces in the mid-1920s, including Perpetua and Gill Sans, that are still widely used today. Mankind has been referred to as the ‘personification of womanhood’. I’m not sure about ‘personification’, but it certainly is an image of womanhood, making it all the more baffling why it's called Mankind. For me, though, it treads a fine line between personification and objectification, and I still can't decide which side of that line I think it falls on. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed