Two works in the Barbican’s exhibition are particularly powerful expressions of the assertion of state power. Hannah Ryggen’s Blood in the Grass tapestry from 1966 depicts US President Lyndon Johnson overseeing his administration's intervention in Vietnam. Johnson is a threatening magenta presence in a cowboy hat; the fields of Vietnam are tufts of lush green in stripes alternating with vivid, violent red.

There is a sense that, even when not associated with violence of colonial power, tables and desks are markers of the authority of the state. They are barriers, and they often connote hierarchical status. They dominate the spaces in which we as individuals come across the power of the state – the teacher’s desk at the front of a classroom of neatly ordered pupils’ desks, the table with the glass barrier in the benefits office, the raised podium of the judge in court. They put us in our place.

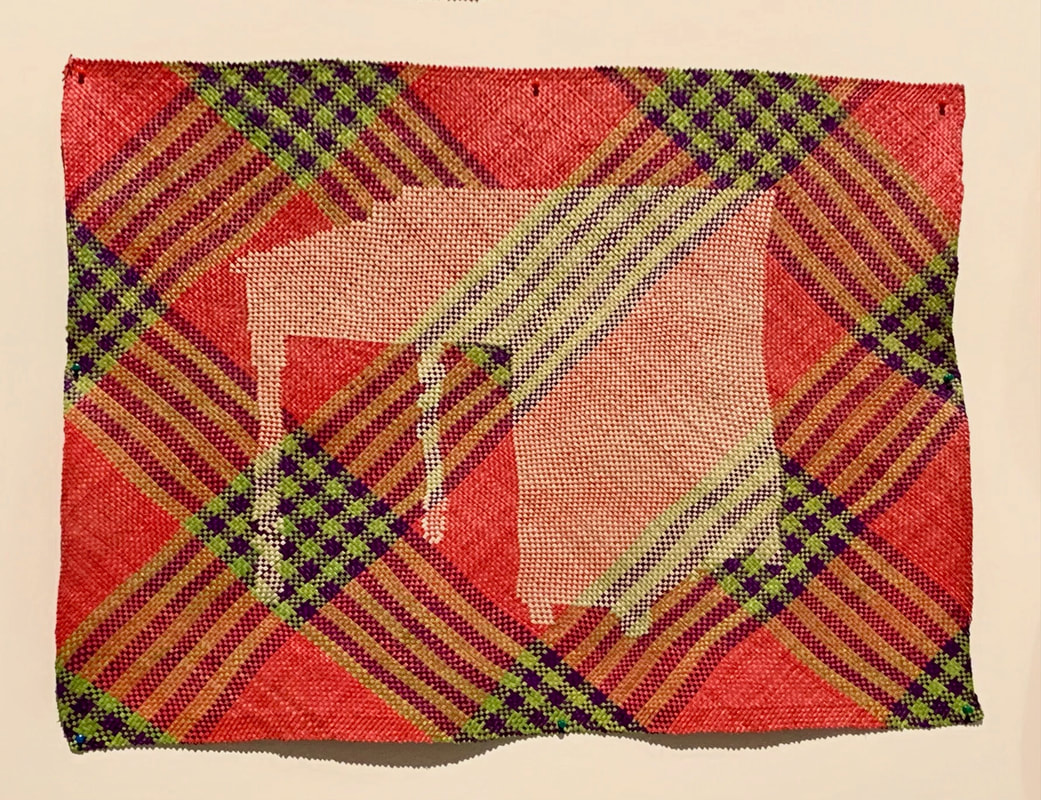

I-Lann took an unusual stance – she chose to include Tikar/Meja in the exhibition, but she made a statement and requested that the Barbican display this on a table in front of her work. In that statement, she says that she was ‘deeply troubled’ by the accusations directed at the Barbican. To withdraw or to participate suggested to her a binary choice that is the antithesis of what her work is about. Tikar/Meja is a work that recognises not just the violence of administration but the other forces at play, including censorship. I-Lann writes: ‘At the table, through tables, through administration, through education systems, officiated histories – through institutions. The actions performed at these metaphoric and literal tables enter the mind and become inherited…. The mat draws from other power systems and calls for people to share a platform together.’

Unravel: The power and politics of textile art is at the Barbican Centre in London until 26 May 2024.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed