Sex and intrigue at the Brompton Boilers

H.V. Morton, In Search of London, 1951

Two years ago, one great thing about the David Bowie fever at the V&A was that it enticed people in who might not otherwise have considered visiting the museum. In spite of Morton's generous description of South Ken in 1951, the area isn't now often seen as one catering to 'different mentalities'. As Welcoming Ambassadors, my colleagues and I frequently were approached by visitors who had never been to the V&A, who had timed tickets to enter the Bowie exhibit in an hour, or in twenty minutes, and wanted to know what could they see in that time. It made for some fascinating ‘moments of shared happiness’ (as our mentor and colleague Glyn Christian calls them) and for some challenging moments as well, as we tried to identify which of the many collections in the Museum would spark the interest of a total stranger.

I had a couple ask me for advice on what to see for two people who had never met each other. They were young and sparky, and as I described the collections I saw their eyes light up on certain ones. (They settled on Architecture and the 20th Century Gallery.) You have to admit the Museum is an inspired choice of destination for a blind date.

I suspect many who don’t know the museum think of it as a stuffy Victorian institution, with objects encased in glass on dark shelves. This stuffiness is well illustrated in a passage from Thomas Crofton Croker’s A Walk from London to Fulham (1860), in which he described the collections of the V&A (then the newly opened South Kensington Museum) in a way that makes a visit seem more worthy than enjoyable:

“There are specimens here of ornamental art, an architectural, trade, and economical museum; a court of modern sculpture, and the gallery of British Art… the whole designed with the view of aiding general education, and of diffusing among all classes those principles of science and art which are calculated to advance the individual interests of the country, and to elevate the character of the people…”

Yet even back then there was something steamy about the locale. Around the time the Brompton Boilers were built (a nickname for the temporary buildings, used disparagingly by the leading architectural journal of the day, The Builder), Croker described the Brompton area as the locale for illicit activities:

“Brompton was formerly an airy outlet to which the citizen, with his spouse, were wont to resort for an afternoon of rustic enjoyment. It had also the reputation of being a locality favourable to intrigue.”

The possibilities for intrigue continue today. Of course, everyone’s taste is different, but one of my favourite pieces to inspire misbehavior is in the Sculpture galleries, in room 21: an Art Deco fireplace with a bronze relief by Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885-1934). The fireplace is considered one of the most important features in Mulberry House, in Smith Square, Westminster, designed by Edwin Lutyens. The house's renovation in 1930 was, according to the V&A's description, considered to be 'one of the finest achievements of a fruitful collaboration between interesting and enlightened patrons, an innovative architect and a painter and sculptor.'

The relief shows a naked couple part-embracing, part-fleeing a crowd of society ladies looking on in fascinated outrage. It was commissioned by Lord and Lady Melchett (Henry and Gwen Mond) as a reference to the untraditional relationship they enjoyed with the writer Gilbert Cannan.

'The bronze itself is a very delicate piece of modelling, and seems – if one must find a meaning for it – to represent “Scandal”. The central pair of nude figures – the lovers – while they make an interesting wall pattern, are a very expressive piece of modern sculpture, the angularity of which seems to heighten the emotion. The other figures in the background, making a rich texture with their clothes, are, one supposes, discussing and criticising the lovers – a very proper satire on the ordinary uses of the drawing room.'

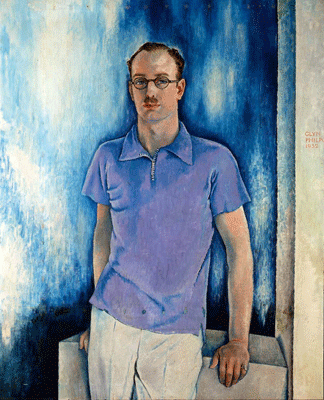

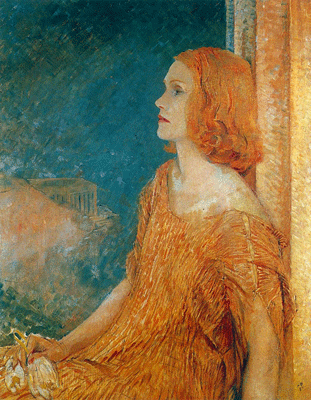

The story behind this work is one of sexual openness and intrigue and is perhaps more steamy than the sculpture itself. Gwen Wilson, an artist from South Africa who had come to London to study at the Slade, and writer Gilbert Cannan were lovers who lived together in a studio in St John’s Wood. Gilbert had recently divorced from Mary Barrie, having been a co-respondent in the much-publicised divorce between Mary Barrie (a former actress) and J.M. Barrie (author of Peter Pan) in which mary claimed the marriage had not been consummated. Mary and gilbert's marriage itself didn't last long, apparently due to Gilbert's affair with the then 19-year-old Gwen.

The story goes that Henry Mond, wealthy heir to a finance business, had a motorbike accident outside the St John's Wood studio in 1918, and Gwen found him injured and helped nurse him to recovery. Mond moved in with Gwen and Gilbert and became their lodger, and eventually, lover (of Gwen) in an open ménage a trois. Two years later, while Gilbert was away on a lecture tour, promoting the work of his friend D.H. Lawrence, Henry and Gwen married. Gilbert, Henry and Gwen continued to live together after Gilbert's return. However, as curator Eric Turner reports, the Mond marriage precipitated Gilbert’s 'final, catastrophic and irreversible mental breakdown', and he was admitted to The Priory hospital in south London, where he remained from 1924 until his death in 1955.

Intrigue doesn't always turn out well. But no doubt it was all good fodder for the gossip columns of the time.

For more details and images of the Mulberry House Art Deco interior, see Eric Turner, 'Art Intimates Life: The Mond "Ménage à Trois"', Apollo Magazine, Sept 2009, http://theesotericcuriosa.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/art-intimates-life-mond-menage-trois.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed