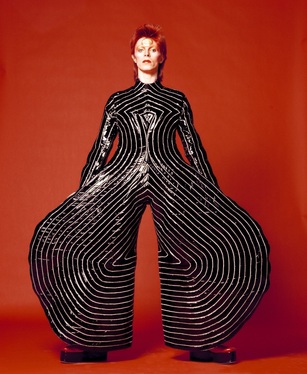

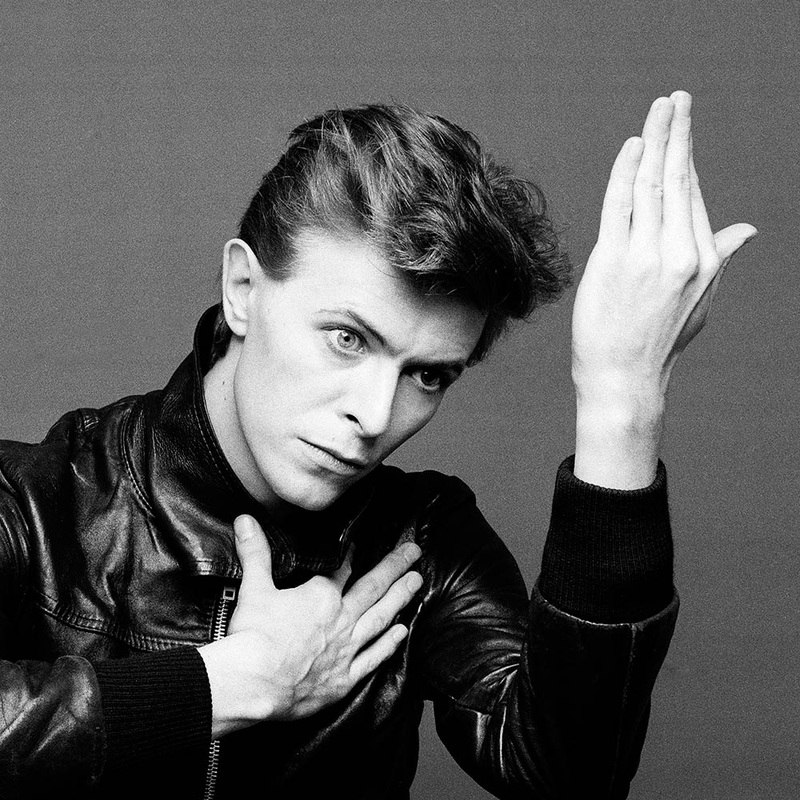

| Bowie was a role model for all the geeky outsiders in school who wondered how to be true to themselves and survive. He played with his image, wearing his hair very short at a time when that was loaded with significance, and dyeing it bright orange. He wore outrageous costumes – like the jumpsuit he wore to perform ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops in 1973. He described this costume as an ‘ultra-violence in Liberty fabrics’ – ultra-violence being one of the pursuits of the main character in Clockwork Orange, a book Bowie greatly admired. Writer JG Ballard described Bowie as ‘an astronaut of inner space’. He was fascinated with Orwell’s 1984 and sceptical that our obsession with technology would bring about progress. |

Rebel rebel, your face is a mess. It makes me wonder where the future Bowies will come from.

See a trailer for the film of the David Bowie Is exhibit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed