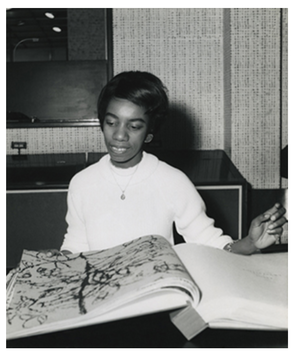

Althea McNish

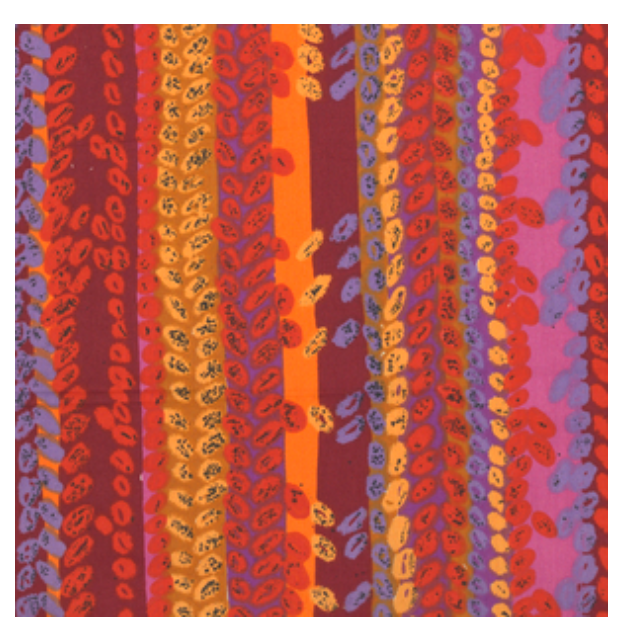

| When you look at Golden Harvest, you see Britain transformed by the colours of the Caribbean. Althea McNish (b. 1933), who designed the textile while a student, was inspired by walking through wheatfields near the Essex home of her tutor, Edward Bawden. She had come from Trinidad in the 1950s with her mother, to join her father, who was already working in Britain. As a child, Althea used to help her mother with her dressmaking business – not sewing but sketching – and had already developed as a painter before leaving Trinidad. Initially planning to study architecture, she instead enrolled at the London College of Printing, studying screen printing before shifting to the Royal College of Art. There she was urged by Eduaordo Paolozzi, then a teacher at the College, to apply her knowledge of printing and her love of design to textiles. Soon after graduating, her work was spotted by the head of Liberty's, and she received her first commissions that set her off on an international career producing fabrics not only for Liberty's but for designer Zika Ascher for fashion house Dior. She became Britain's first internationally known black textile designer. |

Golden Harvest was produced by Hull Traders, an innovative textile firm based in Colne in Lancashire, which specialised in artist-designed, screen-printed textiles. The Whitworth Gallery, which holds many of McNish's designs, says that Golden Harvest became their all-time best-selling design, and continued to be manufactured into the 1970s.

| McNish designed murals for cruise ships, wall hangings for British Rail. She says that the opportunity to discuss her work with people who appreciated it was special to London at the time; she enjoyed the openness to her fresh approach – she describes the tutors and technician she worked with as simpatico with her and encouraging but also suggests that she was on a different wavelength, 'and that was good'. Like fellow textile artist Enid Marx, she felt the relationship with technicians and printers was an important one. She knew the ins and outs of the technology of producing pattern: 'That’s why I was able to go to the factory and I would say “listen you know how I got that so and so and so and so... I made it myself so it’s a kitchen recipe of sorts. This will give you what you want". And they appreciated the fact that a designer could actually come and talk about it ... I challenged them in their own ground and then they wanted to prove to me that they could do it.' |

| Her husband, John Weiss, himself an artist and designer, says of Althea that 'she introduced tropical color into the field of British textiles, which at that time had been polite, sombre'. (CC) McNish's story is that of the African diaspora: her ancestors had been taken in the 1700s from Africa to Georgia, in the US, and later settled in Trinidad. The Whitworth Gallery suggests that her career as a prominent Black and female artist in 1950s Britain contributed to the growing recognition of multiculturalism within the design world and British culture. He describes it as a form of 'return payment', her textiles as 'a good symbol of the special part of the relationship between the slavery world and the home country. In other words, here was some of the, you might call it, the return, a return payment in quite a different way from whatever might have been thought.' McNish was part of the Caribbean Arts Movement. Weiss notes that because she works in textiles, her work has had a considerable impact on British life, perhaps more than other Caribbean artists because of the role that textiles (furnishing fabrics in particular) have in our daily life. The work of Althea McNish features in the BBC programme 'Whoever Heard of a Black Artist', about a project led by artist Sonia Boyce to highlight artists of African and Asian descent who have helped to shape the history of British art.ting |

Christine Checinska (2018) 'Christine Checinska in Conversation with Althea

McNish and John Weiss', TEXTILE, 16:2, 186-199

Whitworth Gallery, 'Trade and Empire: Remembering Slavery', 2008-2009,

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/why-was-cotton-so-important-in-north-west-england/objects/fabric-golden-harvest.html

McNish and Weiss, http://www.mcnishandweiss.co.uk

RSS Feed

RSS Feed